Nature Is Not a Machine

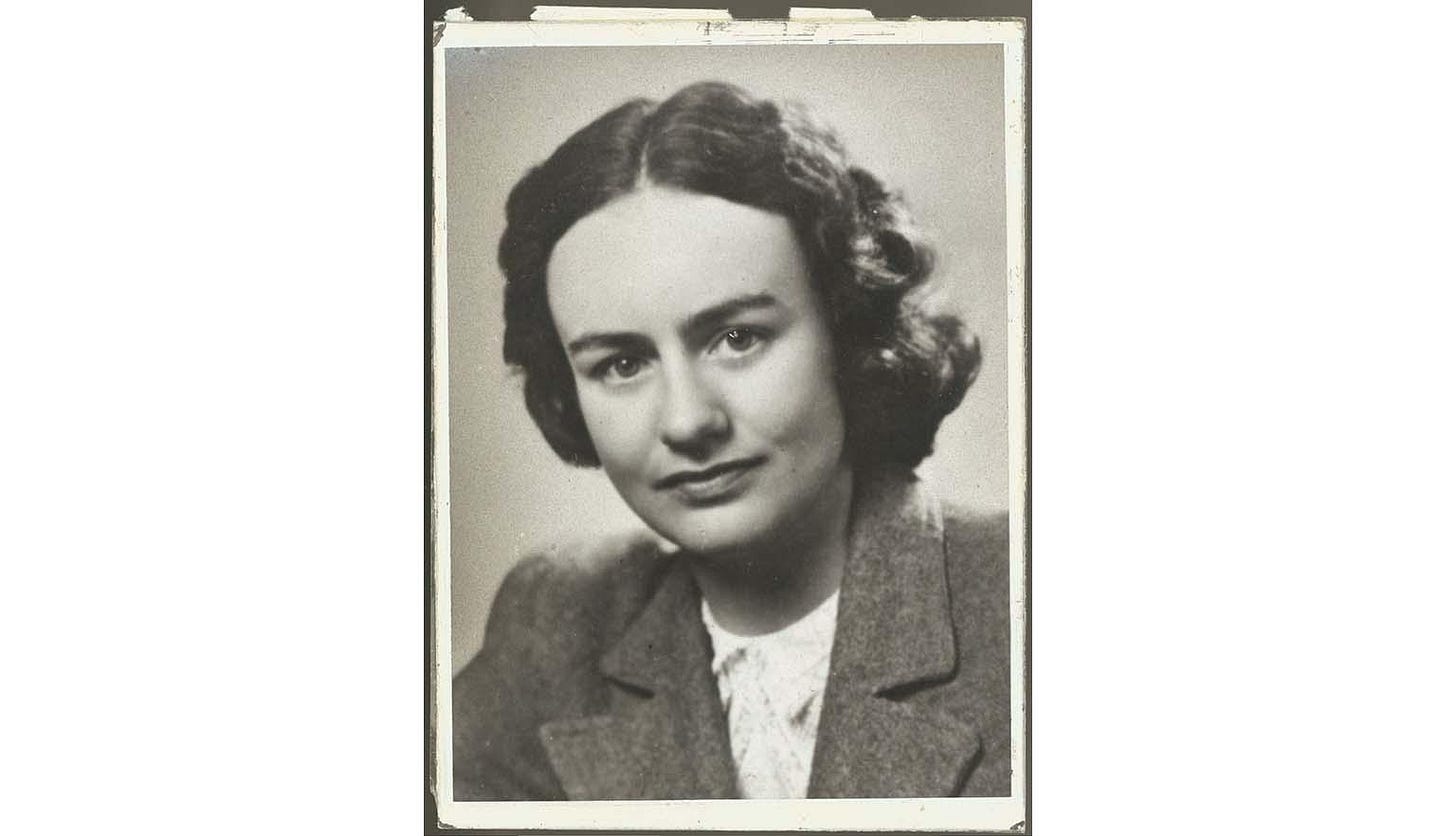

Australian Poetry #3: Judith Wright

Earlier this year, I went for a road trip around regional New South Wales and found myself in New England, where men are men and sheep are nervous. One of the most beautiful places in the world, it’s now associated with the tomato-faced politician who represents it, but in my heart, it’s always linked to the poet Judith Wright (1915-2000). New England will eventually forget the politician, but not the poet’s lines:

“How like a diamond looks the far-off day”

“The intricate and folded rose”

“Only the lovers and the young are dancing”

She worked in Sydney, Queensland, and Canberra, but was born in the rural town of Armidale to a prominent pastoralist family, though it would be more accurate to say that her family employed the pastoralists; in the poem “South of My Days” she memorialises a stockman “old Dan.” Her father had an Aboriginal nurse who taught her about Aboriginal stories and culture. Later in life, Judith Wright was a vociferous supporter of Aboriginal land rights and became close friends with the poet Oodgeroo Noonuccal.

Working at the University of Queensland, she met and married J.P. (Jack) McKinney, a self-taught philosopher who was interested in archetypal and perennial wisdom – themes that would deeply influence her poetry.

She started writing in 1942, when she returned to New England to help her father on the station (what Americans call a “ranch”) and, of course, it was the natural landscape that inspired her. But, in 1965, when asked if she considered herself a nature poet, she replied:

No, I don’t. My real interest, I think, is the question of man in nature — man as a part of nature. The theory of correspondences that Baudelaire brought forward — the question of nature as a symbol of one’s experience has always seemed to me to have a great deal in it.

Before “re-enchantment,” and “new Romanticism” became buzzwords, she herself affirmed this symbolic relationship between man and nature in her essay “Romanticism and the last frontier,” writing against the perspective that sees the world as a vast machine to be measured and exploited:

Nature can no longer be viewed as a machine. It has a living aspect, with which we find ourselves identifying; for, as living beings, we share much with other forms of life. We can perceive, in the change from day to night, from winter to spring, an inescapable correspondence with the process of our own bodies, and we can see those same changes going on in creatures other than ourselves.

Of course, we resonate with the environment and are miserable when this connection is broken. She saw in nature a set of symbols pointing beyond the merely human, and in that aforementioned interview said “I think that anyone who does any deep thinking about the place of man in nature does, at any rate, have his feet on the same path as the mystics have.”

Outside the academy, Judith Wright’s poems are considered Australian classics, picturesque descriptions of landscapes. This is understandable, as she wrote little poetry in the last 10 years of her life, dedicating herself to environmental activism. But don’t miss this mystical connection, the symbolic overtones, the classic themes of life, death, rebirth. You can see all this in the first stanza of “South of My Days”:

South of my day’s circle, part of my blood’s country, rises that tableland, high delicate outline of bony slopes wincing under winter, low trees blue-leaved and olive, outcropping granite – clean, lean, hungry country. The creek’s leaf-silenced, willow-choked, the slope a tangle of medlar and crabapple branching over and under, blotched with a green lichen; and the old cottage lurches in for shelter.

See how the country is imbued with life, how the personal and natural suffer in sympathy – “blood,” “bony,” “wincing,” “lean,” “hungry,” “silenced,” “choked.” Against this cold, warmth is associated with old Dan, who can spin a story

into a blanket against the winter. Seventy years of stories he clutches round his bones. Seventy summers are hived in him like old honey.

Despite old Dan’s stories, the poem ends with melancholy and futility, and goes back to where it began:

Wake, old man. This is winter and the yarns are over. No one is listening. South of my days’ circle I know it dark against the stars, the high lean country full of old stories that still go walking in my sleep.

Those old stories now exist only in dreams. We are given hints of spring but we don’t see it. In contrast to old Dan’s powerlessness (you might say his impotence) the powers of regeneration are linked to motherhood. In “Train Journey,” the narrator looks out the window of the railway carriage and sees “under the moon’s cold sheet / your delicate dry breasts, country that built my heart.” Here we have the earth-as-mother archetype, but in “Woman to Child” the poet becomes the Great Mother herself, creating the world ex nihilo:

You who were darkness warmed my flesh where out of darkness rose the seed. Then all a world I made in me; all the world you hear and see hung upon my dreaming blood. There moved the multitudinous stars, and coloured birds and fishes moved. There swam the sliding continents. All time lay rolled in me, and sense, and love that knew not its beloved.

Pregnancy is not just a biological but a cosmic process. In the last stanza, the mother is the very source of life and nourishment: “I am the earth, I am the root, / I am the stem that fed the fruit”.

Yet, Judith Wright was aware of sacred ambiguities. Here’s her poem “Ishtar,” which is too powerful not to quote in full:

When I first saw a woman after childbirth the room was full of your glance who had just gone away. And when the mare was bearing her foal you were with her but I did not see your face.When in fear I became a woman I first felt your hand When the shadow of the future first fell across me it was your shadow, my grave and hooded attendant.It is all one whether I deny or affirm you; it is not my mind you are concerned with, It is no matter whether I submit or rebel; the event will happen.You neither know nor care for the truth of my heart; but the truth of my body has all to do with you. You have no need of my thoughts or my hopes, living in the realm of the absolute event.Then why is it that when I at last see your face under that hood of slate-blue, so calm and dark, so worn with the burden of an inexpressible knowledge— why is that I begin to worship you with tears?

By appealing to an archetypal goddess outside any formal doctrine, Judith Wright can better express the uncertainties of religious feeling, especially that of women going through intense bodily experiences such as childbirth and menstruation (I assume that’s what “when in fear I became a woman” refers to) for which traditional religious language is woefully inadequate. The goddess is indifferent, impassive. But she represents timeless experiences: the awe and terror of childbirth, the shock of our changing bodies, our inescapably corporeal fate.

Read in this way, Judith Wright’s poetry isn’t just a celebration of landscape or motherhood. It expresses a tragic, Romantic–ecological mysticism in which nature, body, and divinity form a single symbolic order. The divinity presiding over it — at once absent and present, intimate and amoral, worshipped with tears — is a symbol truer than anything that can be fully captured in a theologian’s proposition.

I really enjoyed this. I need to read more Judith Wright.

Brilliant piece. The way Wright rejected being called a "nature poet" yet insisted on nature as symbolic correspondence is fascinatng. How mechanistic views still dominate environmental discourse even today, when the reenchantment she talked about feels more urgent than ever. Those lines from 'Ishtar' where the goddess is both indifferent and worshiped with tears kinda captures that impossibility of reducing embodied experienceto doctrine.